Month: October 2018

-

You should always name your price first.

You should always name your price first Imagine you are in a market in China and see something you like. You ask what the price is and the lady gives you a figure which seems a little steep to you. In a market, you can be sure the price she has told you is way…

-

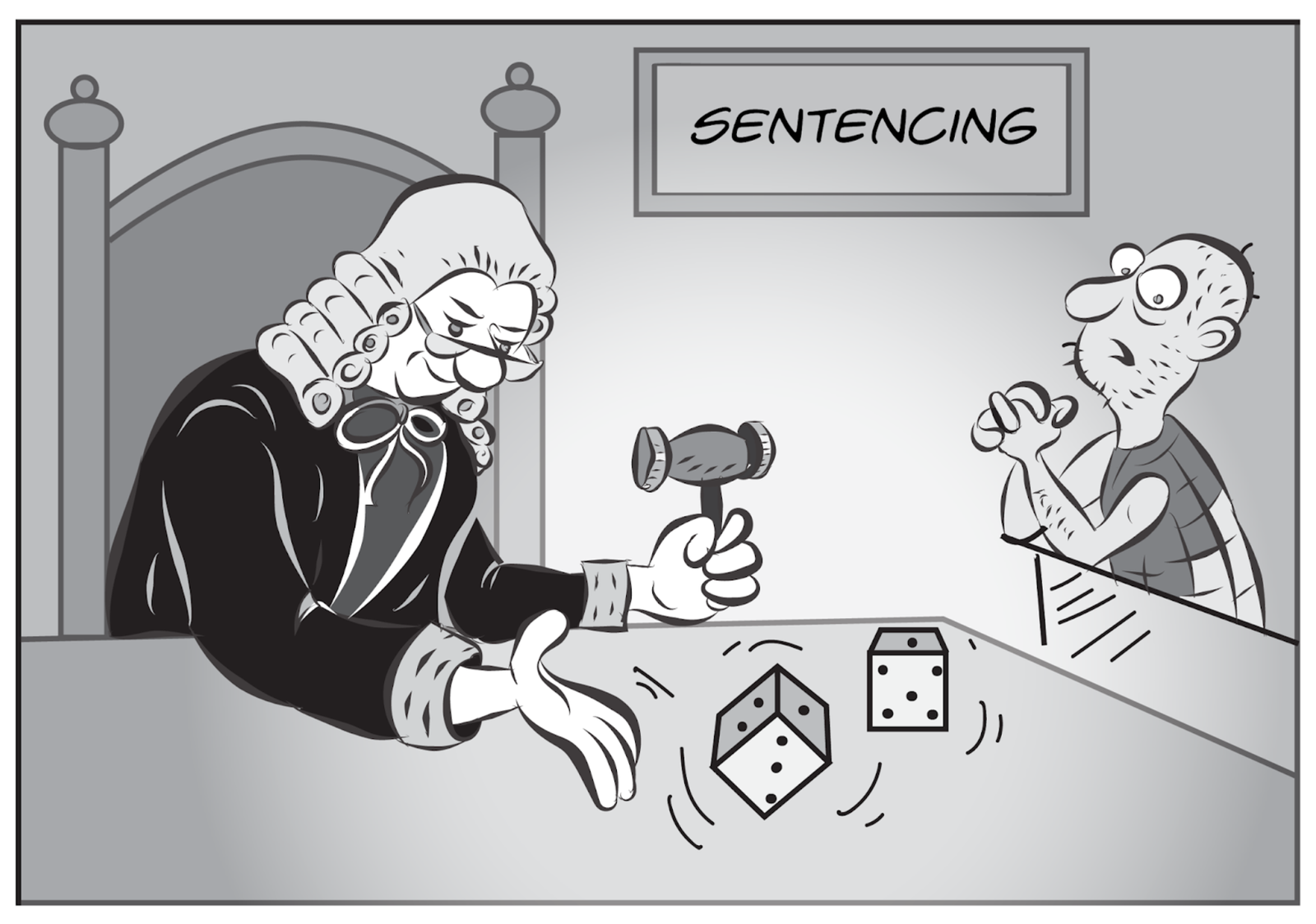

Judges should not play with dice

Judges, if they were allowed to play with dice, could be influenced by those dice when deciding on prison terms. I will explain how, but first I want to ask you a question: Do you think there are more or fewer than 15 countries in Africa? Think about it for a moment. More than 15…

-

Being stoned does not necessarily make you a bad eyewitness

Being stoned does not necessarily make you a bad eyewitness. A recent study by Vredeveldt et al has shown that witnesses to a crime could pick the thief out of a line up just as well if they had been smoking marijuana as if they had not. Participants were asked, either before or after consuming…

-

You are useless at statistics.

You are useless at statistics. Yup. Useless. Intuitively, I mean. You may well be able to sit down and work out the actual objective chances that something will happen, but that is not how the brain naturally works. Your brain works in stories and pictures, not complicated mathematics. If you watch somebody tossing a coin…

-

A smile won’t make you happier if you are being watched

In the last post I mentioned the feedback your brain receives when you smile. Effectively, it thinks, “Hmm. I’m smiling; I must be happy”, and you actually become happier. This was shown in a famous study by Fritz Strack in 1988. However, attempts to replicate this experiment were not always successful. Some worked and some…

-

If you smile you will feel happier.

If you smile you will feel happier. We think of our facial expressions and body language as being caused by our feelings and attitudes. However, it goes the other way too. If you smile, that tells your brain that you must be happy. Fritz Strack asked his participants to either hold a pen horizontally between…

-

Token Gestures Can Lead to Big Changes in Behaviour

Token gestures can lead to big changes in behaviour If we show some small commitment to a point of view, it can greatly influence our future behaviour and opinions. This is why marketers hold competitions where you are encouraged to state why you like a particular product. That small sign of commitment (even if you…

-

Are Christiano Ronaldo and Brett Cavanaugh both Sex Criminals?

Are Brett Cavanaugh and Christiano Ronaldo both guilty of sexual assault? As I write this there are two high profile charges of sexual assault in the news. But can we believe them? In questioning their guilt, some may say I am disrespecting their accusers, who have apparently been through a horrific ordeal. And some may…

-

Fighting Your Prejudices Could Make Them Worse

We all have prejudices. Stereotypes are a necessary part of our psychological make-up and prejudices are an unfortunate side effect of these. However, we are sentient beings who should be able to rise above these prejudices, see them for what they are, and act in a fair and unbiased manner. Right? Weeeell… sooooort of. Imagine…