Month: June 2018

-

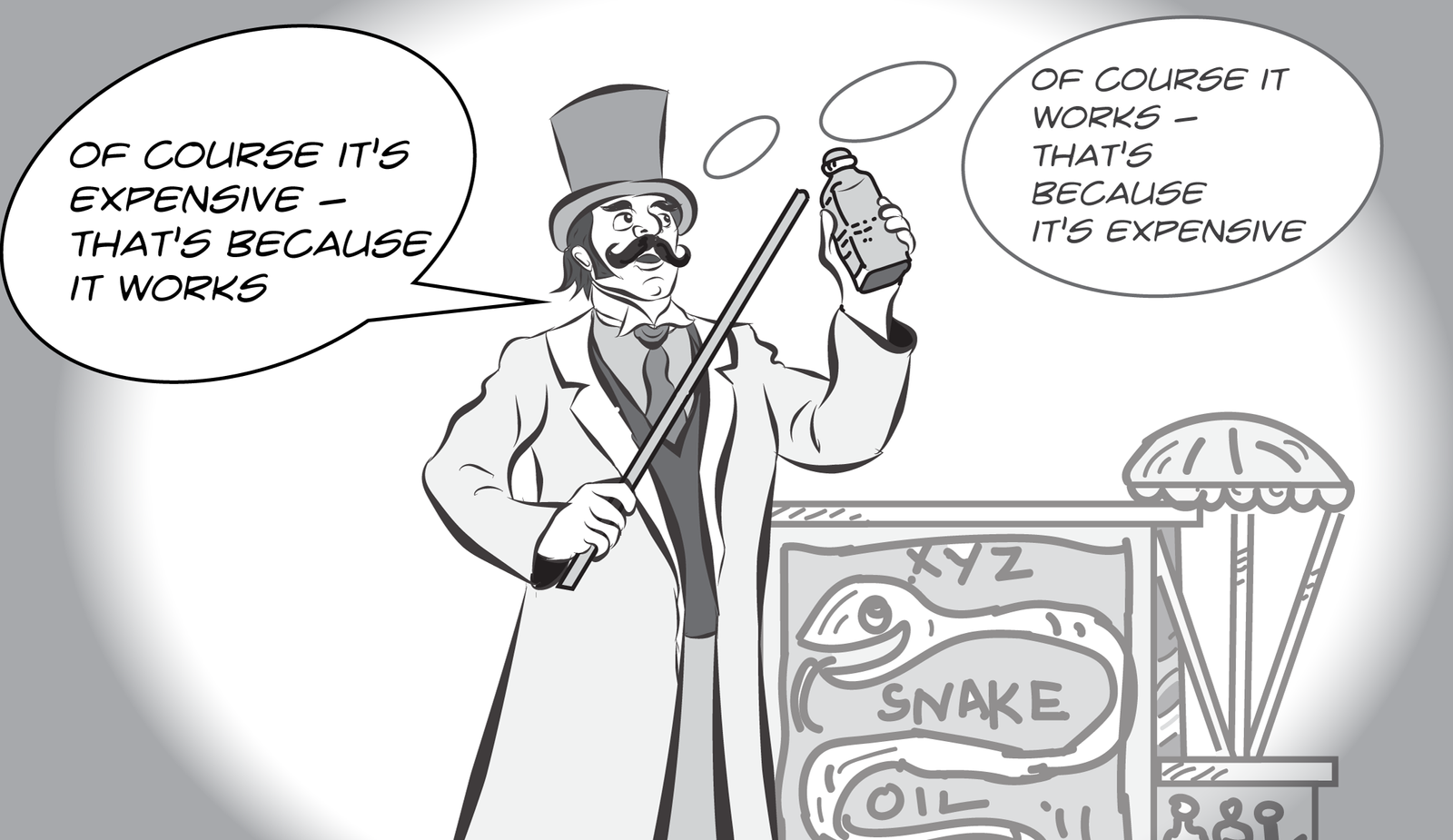

Repetition Creates Belief

Repeating a lie makes it true. That statement is, of course, patently false; repetition cannot stop a lie from being a lie. But it can make people believe the lie. This is how… If a statement is repeated it creates a sense of familiarity in the person who hears or reads it for the second,…

-

Medicine should taste bad

Research has shown that, because we think medicine tastes bad, horrible medicine can work better than nice medicine! There is a very simple reason why medicine should taste bad, and it is a word which generally gets a bad rap: placebo. A placebo effect is where our brains fool us into feeling something that isn’t…

-

Fake News

How Does Fake News Work? What is Fake News? I don’t recall hearing the term “Fake News” before a year or so ago, but now it is everywhere. Donald Trump makes many claims that journalists are inventing fake news against him, whilst his detractors accuse him of propagating fake news himself. So what is fake…